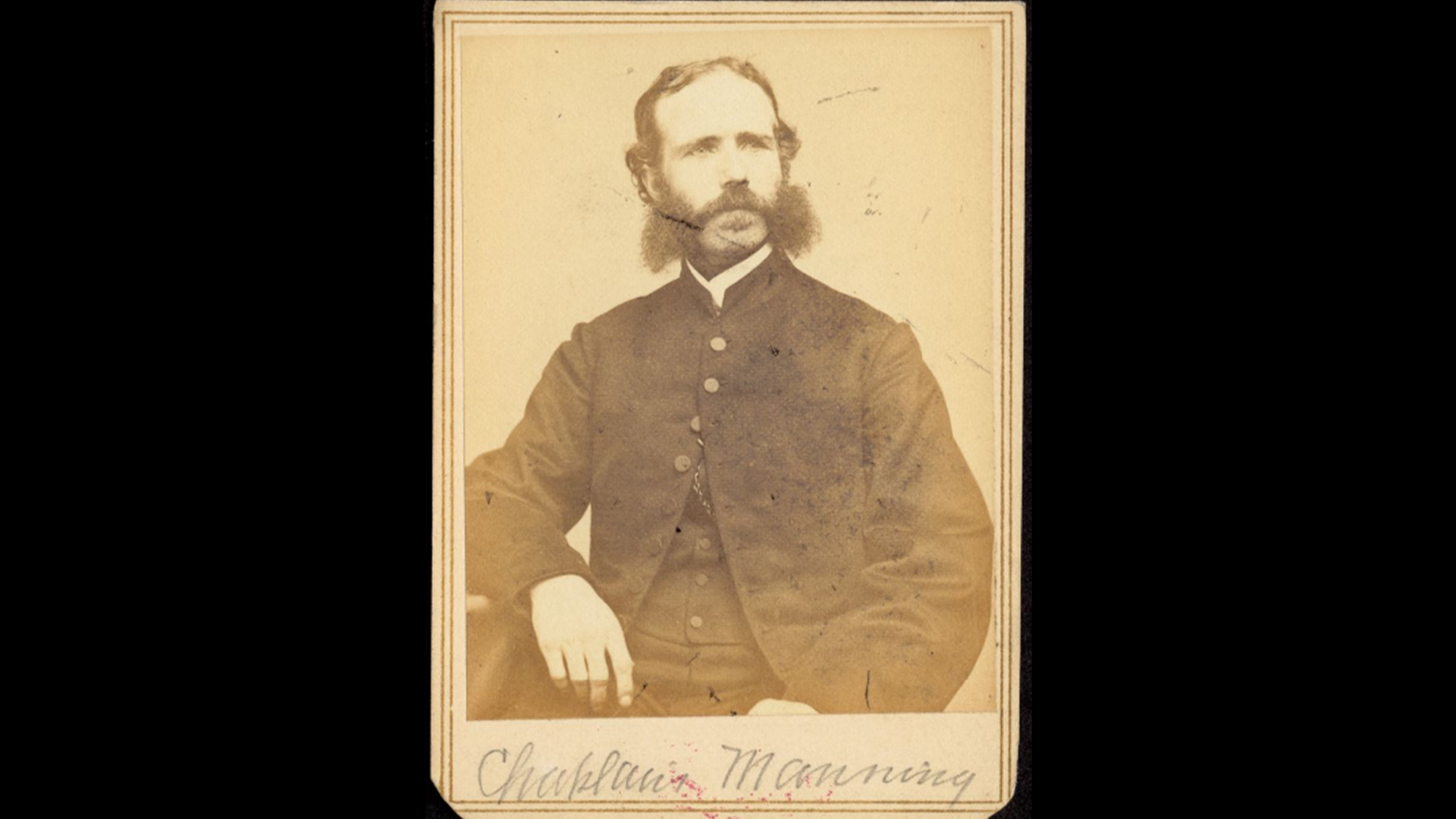

The Reverend Jacob Merrill Manning, Old South’s 15th Senior Pastor was a staunch abolitionist. He was eager to serve as a chaplain for the Union army during the Civil War, and he was assigned to the 43rd Massachusetts Regiment (also known as the “Tiger Regiment”) in November of 1862. During his eight-month tenure as chaplain, Manning wrote regular letters to the Boston Journal describing life in the Union Army (Silfen, 2022). He also used these letters as a vehicle for communicating his thoughts about the social and spiritual issues of his day. I have highlighted a few key themes and observations that emerge from his letters.

The poor living conditions: Manning’s letters do not shy away from describing the appalling living conditions for the 43rd regiment. In his letter dating November 10th, 1862, Manning described conditions on the steamship “Merrimack,” which was transporting the soldiers down to North Carolina. The journey did not begin well; most of the men' s belongings had been left behind on shore. Manning noted that it was too dark for people to see one another, and “the air was so impure that every breath seemed like a dose of poison.”(Manning, 1862, p. 2). The sleeping berths were too narrow to accommodate three men, yet four people had to squeeze into every berth. A slippery and unsteady deck made it difficult to walk or eat, and Manning believed that many lost their lives due to the poor quality of the beef they were served on board the Merrimack.

Grave plundering & stealing: Manning was disturbed by more than the deplorable living conditions. Soon after the regiment arrived in North Carolina, Manning was shocked when he saw Union soldiers break into a family tomb on a nearby estate and steal various treasures. While the soldiers did not lack food, this did not stop them from spending their nights stealing sweet potatoes, persimmons, and poultry from southern homes. Manning lamented that many “had a passion for bringing home a relic.” (Manning, 1862, p.4)

Worship during a war: Attendance at worship services was not mandatory for the regiment, so Manning was pleased to note that many soldiers still chose to attend the makeshift religious services that were held at the camps and on board the Merrimack. He describes “hearty singing,” reverent silences, and enthusiastic prayer responses. In one letter, he wrote: “Seldom have prayer and praise ascended from a fouler dungeon, but no one could be there without feeling that the pitying God accepted the sacrifice.” (Manning, 1862, p.2) As a preacher, Manning encouraged the men to worship God by “preserving their cheerfulness and accepting their hardships.”

Old South’s contribution to the war effort: Manning noted that members of the Tiger Regiment benefited from the work of Old South’s volunteers. He referred to the “delicate hands” (Manning, 1862, p.4) that prepared bags of coffee and tea for men in the regiment. The men were able to enjoy as much tea and coffee as they liked.

Struggles & convictions: Jacob Manning did hesitate to share his own struggles with readers of the Boston Journal. In a letter dated December 30, 1862, Manning wondered how the soldiers could hold onto a faith in God during the horrors of battle. He asked, “What are the effects of campaigning upon those higher faculties of the soul in which his nobleness most truly resides?” (Manning, 1862, p.5) Manning admitted that he did not have an easy answer to this question, but he vowed to continue to grapple with it. In a February 1963 letter, Manning confessed to wanting to return home but expressed his deep conviction that he was in the right place and that justice would ultimately prevail:

"I love my home and parish, and would weep tears of joy to be back in them to-day; but I feel and trust that every relative, friend, and parishioner of mine will also feel, that the the place for him to be in is the place which permits him to do most toward crushing down this great Southern wickedness, and purifying the entire nation from its deep-seated sins, so that he may help prepare the way for that reign of righteousness which is to fill the earth." (Manning, 1863, p.10)

A startlingly harsh truth: Manning noted on more than one occasion that formerly enslaved blacks were grateful to be prisoners of the Union Army. In a letter dated January 6, 1863, Manning related a story about an enslaved man that his regiment had captured during a battle. The captured man “expressed great delight at being taken prisoner, as he would now have the opportunity to escape from his master” (Manning, 1862, p.7) and he voluntarily stayed with members of the regiment where he had lighter duties.

Fears for the future: On January 28, 1863, Manning expressed his joy about Lincoln’s recent issue of the Emancipation Proclamation. But he also eloquently wrote about his fears for men and women who had only ever known a life of enslavement; he worried that they were not ready to face the responsibilities that come with freedom. He wrote: “Schooled for ages in the terrible school of bondage–how little the poor African can anticipate of the ceaseless vigilance, toils, and hardships which are necessary to the blessedness of personal liberty!” Manning also pleaded: “And the dear Christ give us charity if we forget that our sins are the cause of our brother’s weakness, to look kindly on his flattering endeavors; to help him forward with our encouragement, and not push him backward by our indifference and sneers while he stumbles forward with such power as slavery has left him…” (Manning, 1863, p.8).

A heart for economic justice: Manning’s desire for economic justice and equality in the US is evident throughout his letters. In a letter dated February 13, 1863 he noted that there were pleasant school houses for children of the wealthy, “but a school house, tasteful and commodious, for the children of the poor and adapted to the purposes of instruction, I have not yet seen since landing in North Carolina.” Manning also lamented that the more poverty stricken areas did not have attractive houses of worship.(Manning, 1863, p.9)

References:

Manning, J.M. (1862-1863). [Transcribed Articles & Letters to the Boston Journal]. The Congregational Library & Archives (Box 37, Folder 3), Boston, Massachusetts.

Silfen, K.S. (2022). The really useful guide to the senior ministers of Old South Church in Boston. Pilgrim Press, 2022.